Longtime ±«ÓătvBoard Member Reflects on Breaking Conventional Rules to Carve Lifetime of Business Success

Renowned Tuscaloosa, Alabama businessman Fred Hahn’s association with Mississippi College almost ended before it had even begun.

During a recent visit with representatives from his alma mater, the 94-year-old entrepreneur recalled how he made a name for himself on MC’s B-team basketball squad – before he had attended his first class.

Coach Jim “Mac” McCloud’s round-ballers were facing Millsaps College at City Auditorium, and Hahn, who was in the process of transferring from Hinds Junior College, suited up at center.

“I didn’t even know my teammates,” he recalled. “Millsaps had a big ol’ clumsy center. Two or three minutes into the game, they grabbed a rebound and started a fast break. Their center was running backwards, so I bent over and he stomped over me and hit the floor. Then he started kicking me with his feet.

“They kicked us both out of the game. I hadn’t even enrolled yet, and I figured I was going to get thrown out of school.”

McLeod instructed Hahn to go downstairs to the locker room, where legendary Coach Stanley L. Robinson, for whom the Choctaws’ football stadium is named, would pay him a visit.

“I was scared to death, sitting by myself, waiting on Coach Robbie,” Hahn said. “After about 10 minutes – it seemed like two hours – he came in and sat down beside me, and didn’t say a word. We sat there for I don’t know how long – it was torture for me – and after a while, he turned around and asked, ‘Are you sorry for what happened?’

“I said, ‘Yes sir, Coach, I apologize for embarrassing the school and you and everybody else.’ Which I was. I didn’t start that fight – I just bent over and the guy flew over me. Then he turned to me and said, ‘I think you mean it. That being the case, I would have hit him, too.’”

The ±«Óătvalum grew up on Clinton Boulevard and learned valuable life’s lessons inside and outside the classroom. Although he was smart enough to skip second grade, Hahn admitted he wasn’t much of a scholar in high school – preferring to work in his family’s hospitality business.

“I wouldn’t study,” Hahn said. “We were running the motel with a café, and I was finding other things to do other than study.”

He attended high school classes in what is now the Gore Arts Complex at Mississippi College. Decades later, he was a member of MC’s Board of Trustees when the Christian University obtained the East Campus, including his old school building that became the GAC.

His athletic ability in football, basketball, and baseball earned him a working “scholarship” – a case of lightbulbs was delivered to his third-floor residence hall room and he was required to replace any bulbs that burnt out in the hallway.

“I don’t think I replaced one light,” he said.

He enjoyed typing class, but had trouble with English and physics. He tried his best to pass his classes so he could be eligible to play football, basketball, and baseball.

During midterm break – on the eve of the state basketball tournament – his coach discovered that Hahn had flunked physics class.

“We were already in Vicksburg – that’s where they were holding it (the state tournament),” Hahn said “He threw a fit. He contacted a physics professor and they got me a ‘D-minus,’ provided I would go back and outline the book.

“Someday, I’ve got to do that.”

He managed to survive high school and enrolled in Hinds Junior College in Raymond, where he played football. But legendary Choctaws coach Stanley L. Robinson, who had once coached Hahn’s uncle in baseball, coaxed him to Mississippi College to play baseball. Hahn left Hinds midterm to begin his collegiate diamond career for the Blue and Gold.

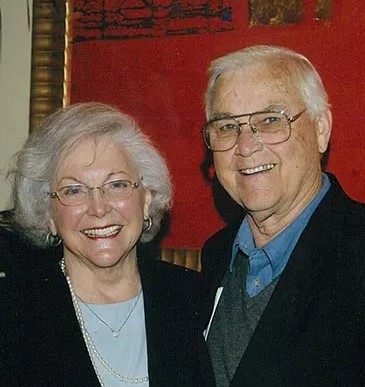

Hahn pitched on the ±«Óătvbaseball team for two seasons. He met his future wife while visiting his brother-in-law in south of Jackson.

“My sister’s husband had gotten out of the Navy, and they built a house in Alta Woods,” Hahn said. “I looked out their window and there was a tall blonde next door mowing the grass.”

The future Helen Hahn was an all-state basketball player who was named “Most Beautiful” at Forest Hill High School. The couple married during his second year in school and remained together for 72 years until her death last spring.

Times were lean for in the young couple’s early days – Hahn had to work nights in a sheet metal shop and hitchhike to school in the mornings. He supplemented their meager income by pitching semi-pro baseball for different teams under an assumed name. One summer, he earned $280 a month playing baseball in Tallulah, Louisiana.

“I would pitch for the college on Friday, then I went somewhere and pitched on Saturday and Sunday,” he said. “We were playing Millsaps on a Monday. I had pitched for the college on Friday, so I knew I wouldn’t be pitching on Monday – it wasn’t my turn. But our other pitcher had gone somewhere and pitched over the weekend, too, so he called the coach over and said he couldn’t go.

“The coach came in the dugout where I was and said, ‘Fred, I know you’ve only had two days’ rest, but do you think you could go?”

Hahn warmed up, started the game, and threw eight shutout innings. The Mississippi College bats were silent as well, so the teams entered the ninth deadlocked at 0-0.

“In the top of the ninth, I sat in the dugout at least 30 minutes. We scored eight runs. I go out for the bottom of the ninth inning. The catcher calls for a fastball and I threw one on the first pitch and you could hear the ligament in my shoulder snap up in the stands. That pretty well did me in.”

He did have a brief – albeit unsuccessful – baseball encore. The manager of the Tallulah team offered him $200 to pitch important games for his team. Not knowing about Hahn’s injury, the coach came calling, and Hahn agreed to help him out.

“I had lost my fastball,” he said. “That first inning, I didn’t get anyone out. They scored five runs on us, and that old man jumps up out of the dugout, spitting tobacco juice. He came out to the mound, reached out his hand to shake hands with me, and he had the $200 in his hand.

“He said, ‘Don’t call me, I’ll call you.’ That was it.”

Hahn went to summer school, made the honor roll, and finished his last two years of college in a year and a half. The 1952 School of Business graduate made the most of his education, working in the Sales and Public Relations Division of the Old North Central Railroad. He served the company for a decade, learning everything he could about business operations during stints in Memphis, Jackson, and Birmingham while working his way up from office manager to chief clerk to commercial agent.

He left the company on his tenth anniversary – the day he received full railroad retirement benefits – and joined Roadway Express as a salesman. Six months after accepting that position, he was offered an opportunity to become partners in a small family-owned trucking company based in Tuscaloosa called Willis Express.

By then, Hahn and his wife had welcomed two children into their family and were living in a small house. A family rift threatened the fledgling company’s viability, however, and the owners offered to sell the entire business to Hahn. At the time, he Hahn didn’t have $100 to his name. Unable to get a bank loan for the down payment, he borrowed the money from a private investor and bought the company.

Hahn turned the business around and began acquiring other interests, including household moving and garbage collection.

“My timing was great,” he said. “That’s when the garbage compactor was coming out. We could set a big container with a motor down at your place, you could throw your garbage in, then we would pack it and go empty it when it got full.

“The first thing you know, I had five garbage companies.”

Hahn’s businesses stretched from Mississippi to Florida. He eventually sold them to Waste Management, who put him in charge of governmental affairs in Alabama and Mississippi.

“The future in the garbage business was that you had to have a landfill,” Hahn said. “The owners could control what they charged to come dump your garbage into their landfill. There were so many environmental requirements that I didn’t want to become involved in that business.”

He stayed on with Waste Management for 15 years. Meanwhile, Hahn’s warehouse business continued to grow. But his success came in unconditional fashion.

Late in life, Hahn entertained a retired business professor who was writing a book. When Hahn told him the story of his business career, the instructor become quiet. “You have broken every rule I’ve been teaching for 50 years,” the professor said. “One of the first: ‘Never start a business undercapitalized.’”

“I didn’t have the luxury to not go bidding the sun to capitalize,” Hahn said. “When you need capital to invest, what are you going to do – rob a bank or inherit the money? I had to break the rules. First, start the business – then make the money.

“It’s different when you don’t have a base to start from. When you’ve got to make it work, you make it work.”

Somehow, Hahn made it work for decades. He built three separate truck lines and sold them all. He teamed with his two sons, Philip and Gregg, to start a new corporation, Seapac, Inc. He even received an honorary doctorate from the University of Alabama and was inducted into the Alabama Business Hall of Fame in 2010.

Through it all, he maintained a heart for Mississippi College. The former longtime ±«Óătvtrustee served on the board’s business affairs and building committees and made major contributions to the university throughout the years. Hahn received the Order of the Golden Arrow Award in 2014 for exceptional performance or leadership beyond the ordinary.

Sign-up For Our Newsletter

Get the latest news about Mississippi College delivered right to your inbox by subscribing to the Along College Street e-newsletter.